Talk Nerdy to Me: Azuka's Dramaturgy Corner (Masculinity in Ancient Greece)

Hello guys, gals, and non-binary pals! My name is Kris Karcher and I am the Dramaturg on warplay. What is a dramaturg you ask? Well, a dramaturg’s job changes with every production, but to put it simply, I see myself as a research assistant to the director, and more importantly, an advocate for the playwright in the rehearsal room. For warplay, being the dramaturg meant doing a lot of digging into the relationship between Achilles and Patroclus, the myths surrounding the Trojan War, and exploring other themes of the play such as Free Will and Toxic Masculinity both now and in Ancient Greece. In this series of blogs, I will be touching on a few different areas of research in order to help contextualize the play you will be seeing in the next coming weeks. Or maybe you’ve already seen the play, and you’d like to know more. That’s great too!

Adequate form. 7/10 — Lucas

As you may (or may not) know, each play in Azuka Theatre’s 2018-19 season has been chosen to examine and dissect masculinity in its perils, its pitfalls, and its very definition. J.C Lee’s warplay is a re-imagination of the relationship between Achilles and Patroclus, two soldiers in the Trojan War. Immediately when I began researching, I was really interested in finding out how the Greeks viewed the construct of masculinity, and how that may have had an effect on our story’s heroes. I quickly found that because Greece was so spread out, finding an all-encompassing definition of Greek masculinity was nearly impossible. Each village and city favored different masculine attributes, proving further that masculinity is a fluid construct rather than a solid set of rules. However, there did seem to be a trend in how Greek culture as a whole shifted over time, which is what we’ll explore in this Dramaturgy Corner.

Early Ethos

In early Ancient Greece, children and adults alike looked to the heroes of their ancient texts like The Iliad and Odyssey to understand what it meant to be a man. In Achilles’ time, if there was indeed a real Achilles, the most important quality of a man was his courage, strength, and bravery. Courage has always been imbedded with being a man in Ancient Greece. The very word that we translate as courage, andreia, comes from the greek word for a male adult, anêr/andros and can be translated as “manliness” (Rubarth 24).

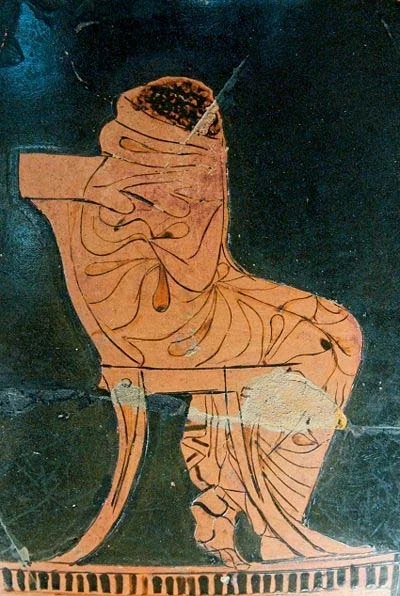

Grieving Achilles. I also hide in blankets when I’m sad. — Lucas

Other attributes of manliness in this era of Greece would surprise you. For example, Achilles is a huge cry baby in The Iliad. He weeps after losing his mistress (for a lack of a better word) to Agamemnon, and continues to sulk for weeks, missing out on countless battles. Of course, he cries in agony again when he loses Patroclus. Men in this time were not expected, as they are today, to not show emotion. It would be seen as incredibly masculine to cry over a deceased loved one, or to overreact and say, kill thousands of men.

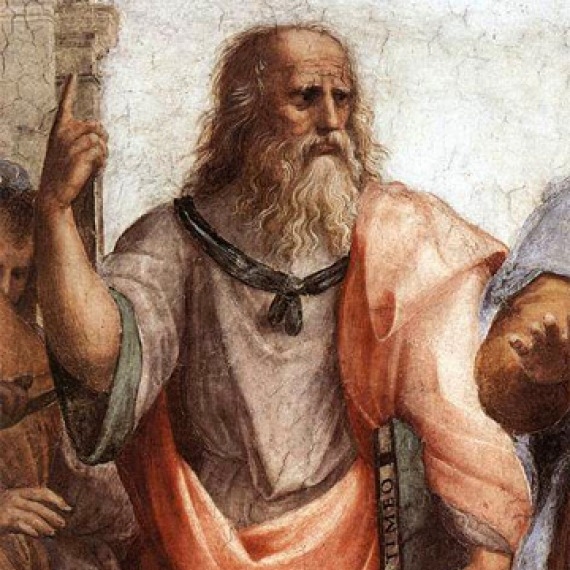

Plato’s Ethos

A major shift in the Greek’s understanding of masculinity came in the age of philosophers like Plato and Aristotle. The rise of philosophy and decline of war resulted in men valuing other attributes such as intelligence, stoicism, and self-control as the ultimate masculine qualities. Instead of celebrating wrath, like soldiers did during the Trojan War, writers and artists became critical of those who could not exhibit self-control (“What the Ancient Greeks and Romans Thought About Manliness”). Playwrights and writers alike started to celebrate heroes like Odysseus and Oedipus who were known for their cunningness and public speaking skills, and would punish their heroes when they exhibited any kind of lack of control (Rubarth 23).

“Smart is the new sexy.” — Plato (Lucas)

Plato’s Symposium states that the most manly men were the thinkers; those who became public speakers or politicians and used rhetoric for political gain. In this domain, speech and critical thought became essential since political rhetoric was competitive. Not only could one beat an opponent in a debate or civil lawsuit, a skilled speaker could ‘unman’ his enemies through the clever use of rhetoric and abusive speech (Rubarth 28).

In a way, warplay is a dramatization of the shift in Greek’s understanding of masculinity through the ages. On one hand you have “A”, who represents the epitome of a man in early Greek ethos, and on the other is “P”, who starts as a thinker; the pinnacle of Plato’s ethos. To see how these worlds collide, you’ll have to come check us out at the Drake before November 18th!

For more on Masculinity in Ancient Greece, you can check out these two sources below:

“What the Ancient Greeks and Romans Thought About Manliness,” The Art of Manliness

Art of Manliness host Brett McKay interviews scholar Ted Lendon about the construct of masculinity in Greek and Roman culture. If interested, listen to the first 20 minutes of the podcast to learn about the ancient Greek notion of manliness, the language of manliness in the ancient world, and how the Greek idea of manliness changed in the age of the great philosophers like Plato and Aristotle.

“Competing Constructions of Masculinity in Ancient Greece” by Scott Rubarth

Odysseus uses wits rather than strength to outsmart the sirens. — Lucas