The SHIP of Theseus

Hello, outcasts and underdogs —

Have you heard of the Ship of Theseus?

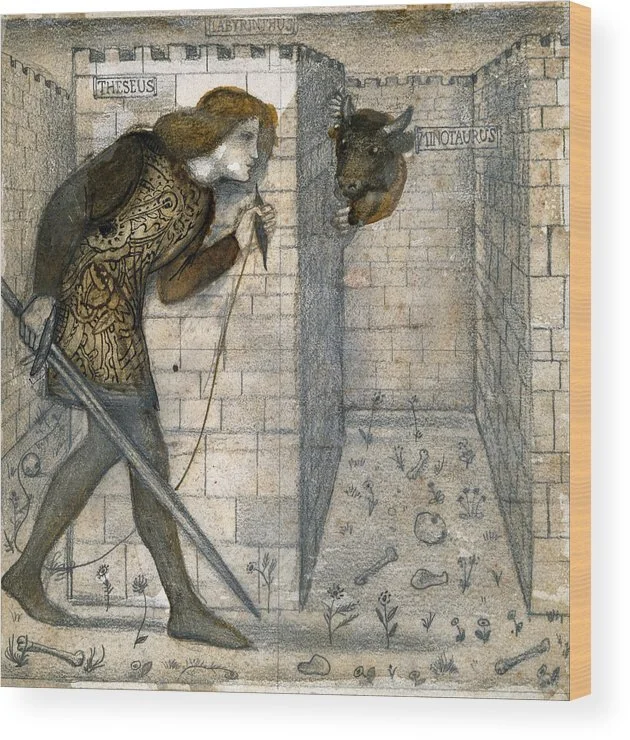

Tile art of Theseus and the Minotaur by Edward Burne-Jones (1861).

Many of you are likely aware of its namesake, from studies of or passing familiarity with Greek mythology — Theseus was a fabled hero, mythic founder of the city of Athens, and especially famous for his journey into the Cretan Labyrinth where he faced the gruesome Minotaur.

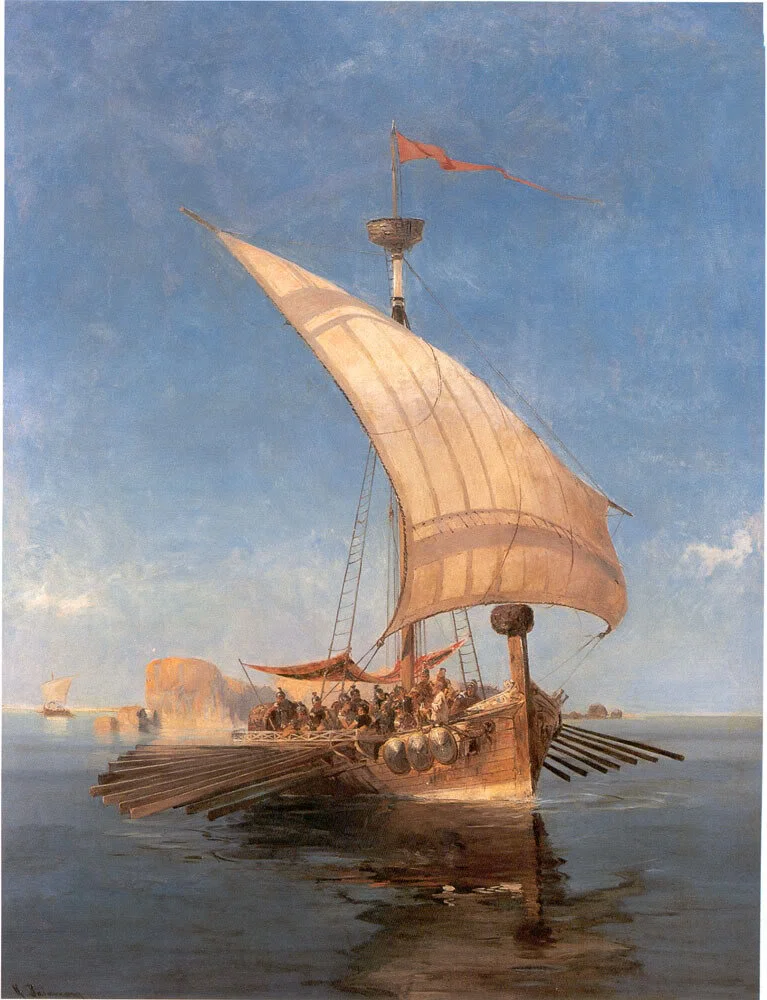

Now, before you start to question if this is a dramaturgical #FlashbackFriday to last season’s Greek myth remix warplay — let’s focus on the ship that, according to Plutarch’s recounting of the hero’s mythical adventures Life of Theseus, Theseus sailed home from the perils on Crete and docked in the Athenian harbor.

If you know the Ship of Theseus, you probably know it as a thought experiment that has now been around for thousands of years (one you might know even if you’ve never heard its name before.) Plutarch writes:

“The ship wherein Theseus and the youth of Athens returned had thirty oars, and was preserved by the Athenians down even to the time of Demetrius Phalereus, for they took away the old planks as they decayed, putting in new and stronger timber in their place, insomuch that this ship became a standing example among the philosophers, for the logical question of things that grow; one side holding that the ship remained the same, and the other contending that it was not the same.”

In so many words: If over time, you replace every single piece of the ship, does it remain the same ship?

A painting of Argo, the ship of Jason and the Argonauts, by Konstantinos Volanakis (1837 - 1907)

Broadly it’s a philosophical question — but specifically it’s a question of identity. What defines the ship as the ship? The parts that make it up? The fact that we call it the Ship of Theseus and it is still a ship belonging to Theseus? Our memory of it? So then, when the question is applied to people, to the philosophy of the mind, the question becomes: What defines us? What makes up our identity so that, if changed, we’d cease...being ourselves?

In SHIP by Douglas Williams, Jeremiah was on his way to set the Guinness World Record for the longest fingernails. He was physically defined by the fingernails, his life was defined by this singular almost-feat — and so he, to an extent, became defined by them.

And now, he doesn’t have them anymore.

Also in SHIP, Nell is a person in recovery, newly sober. As a person in active addiction, her life was, in an addict’s way, defined by the pursuit and satisfaction of her addiction. It bled its way into her family relationships and her reputation, under the influence of these drugs.

And now she doesn’t have them anymore.

Yes, the tale of the Ship of Theseus has a superficial connection to the play’s world; it’s not the Charles W. Morgan that Nell dreams of guiding tourists through, but it is, of course, a ship.

But it also bears a thematic resonance with the fraught identity limbo that Jeremiah and Nell find themselves trapped in. If Jeremiah was defined by this condition since he was young, is he still the same person without them? Is Nell still the same person now that she’s sober?

Nell (Annie Fang) and Jeremiah (Michael A. Stahler) in SHIP // Photo by Johanna Austin/AustinArt.Org

Early in the play, Nell laments to her sister Caitlin, “I don’t know what I have to do to prove I’m a normal person now.”

And later, Jeremiah tells her, regarding the fingernails, “My whole life was about protecting and maintaining these things. Anytime I traveled or attended an event, it was always about the fingernails. And now...I’m just trying to figure out how to be a normal person again.”

Nell replies: “Same.”

They are both trying to escape being defined by past shame. They are both having pieces of themselves removed and replaced and wondering what that now means for who they are to themselves and to the world.

In that way, our next show, A Room at the Flamingo Hotel by Lena Barnard shares a thread.

In the alternate noir world of Flamingo Hotel, in which an actual statue is king, a political movement sees citizens turning themselves into statues.

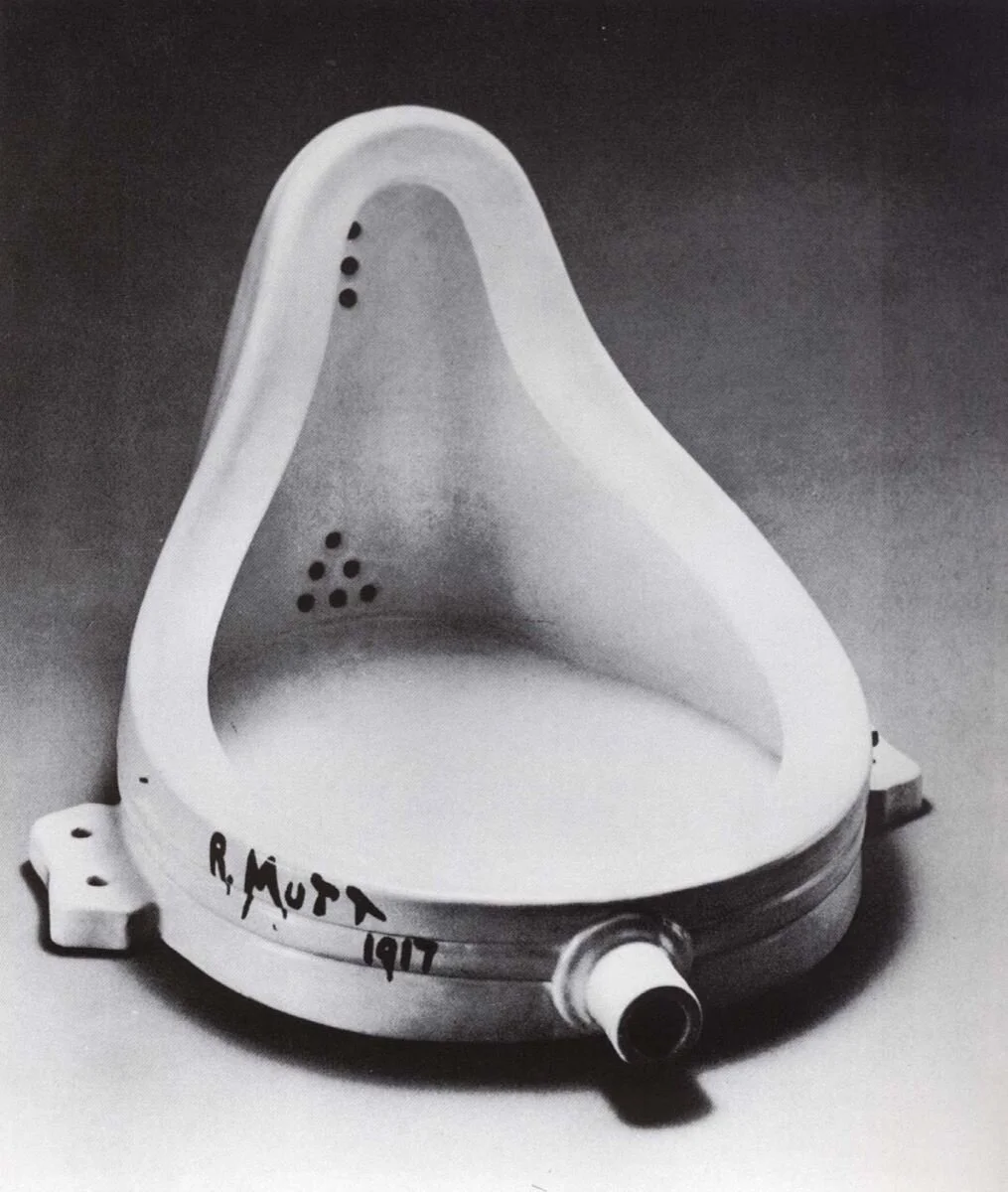

Image of Marcel Duchamp's Fountain, 1917, via Wikimedia Commons.

Questions of definition and identity are already staples of the art world — for instance, the urinal that became Duchamp’s infamous Fountain. In many eyes, that is now a work of art. But to some critics, it’s still just a dirty urinal. How is that change defined?

In Flamingo Hotel, living human beings turn themselves into art. They, in a way, sacrifice their humanity, replace the previous parts of themselves to create a new statement. And the same question arises: how are they now defined? What side of that limbo are they on?

Think of a way that the Ship of Theseus can be applied to your life. How, over time, have parts of you been replaced, or lost, or changed — that made you question your identity?

And, if you have an answer: is the Ship of Theseus the same ship after all those years? We would love to hear from you.

You might say Nell and Jeremiah are, in SHIP, ships themselves.

And in this world premiere production, you get to see their maiden voyage! But act fast: the show only runs until this Sunday, March 15.

You can reserve your tickets for SHIP, A Room at the Flamingo Hotel, or both with a Season Package, now.