"Be a Man Among Men": On LGBT Soldiers in the U.S. Army

James Kern & Jeff Gorcyca in warplay

warplay features two gay men during wartime -- two gay men headed to that war. Immediately, in America, this brings up a lot. We have a complicated history with LGBT service members; we have a history with our perceptions and expectations of what a soldier should be, or can be, a question also grappled with in warplay. Now, as discussed in dramaturg Kris’ guest blogs, those ideas looked very different in Ancient Greece; masculinity in particular carried very different implications and “homosexual behavior” was even encouraged in the army. But warplay is still not rooted in any specific time or place. And as a modern audience, we can’t help but view it through a modern lens, especially with the repeal of Don’t Ask Don’t Tell during the Obama administration, and President Trump’s attempts to put a ban on transgender soldiers. So, let’s look briefly at America’s relationship with queer people in the military, and what warplay might tell us about it.

“Homosexuality is incompatible with military service. The presence of such members adversely affects the ability of the Armed Forces to maintain discipline, good order, and morale; to foster mutual trust and confidence among the members; to ensure integrity of rank and command; to facilitate assignment and worldwide deployment of members who frequently must live and work in close conditions affording minimal privacy; to recruit and retain members of the military services; and in certain circumstances, to prevent breaches of security.”

So stated Directive 1332.14, issued in 1981 by the Department of Defense. What it seems to be implying, in so many words, is that that “homosexual behavior” would be a distraction. It comes across, when written in its very professional language, as an attempt at a purely practical defense of anti-gay policy, which is probably why it’s employed so often. To an extent, regardless of the validity of what it’s saying, it succeeds at that. But obviously, there’s something deeper to the sentiments against LGBT soldiers, an emotional opposition -- rooted in something a bit more primal than practical.

In his book Antigay Bias in Role Model Occupations, E. Gary Spitko addresses this in a chapter called “Defending the Masculine Identity of the Military.” He writes that “the concern with ‘effeminate’ gay soldiers focuses specifically on how such effeminacy might undermine the military’s masculine image: the concern does not reflect a wider anxiety over gender nonconformity.” He points to marines as a sect that appear particularly concerned with this image.

“One marine private who predicted in December 2010 that repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell ‘won’t be totally accepted’ explained this way the disconnect he saw between the gay male identity and the marine’s masculine identity: ‘Being gay means you are kind of girly. The Marines are, you know, macho.’”

There is a very specific image associated with “soldier.” Spitko blames “the set of stereotypes that label both women and gay men as too passive and weak for combat” as the major obstacle to inclusion.

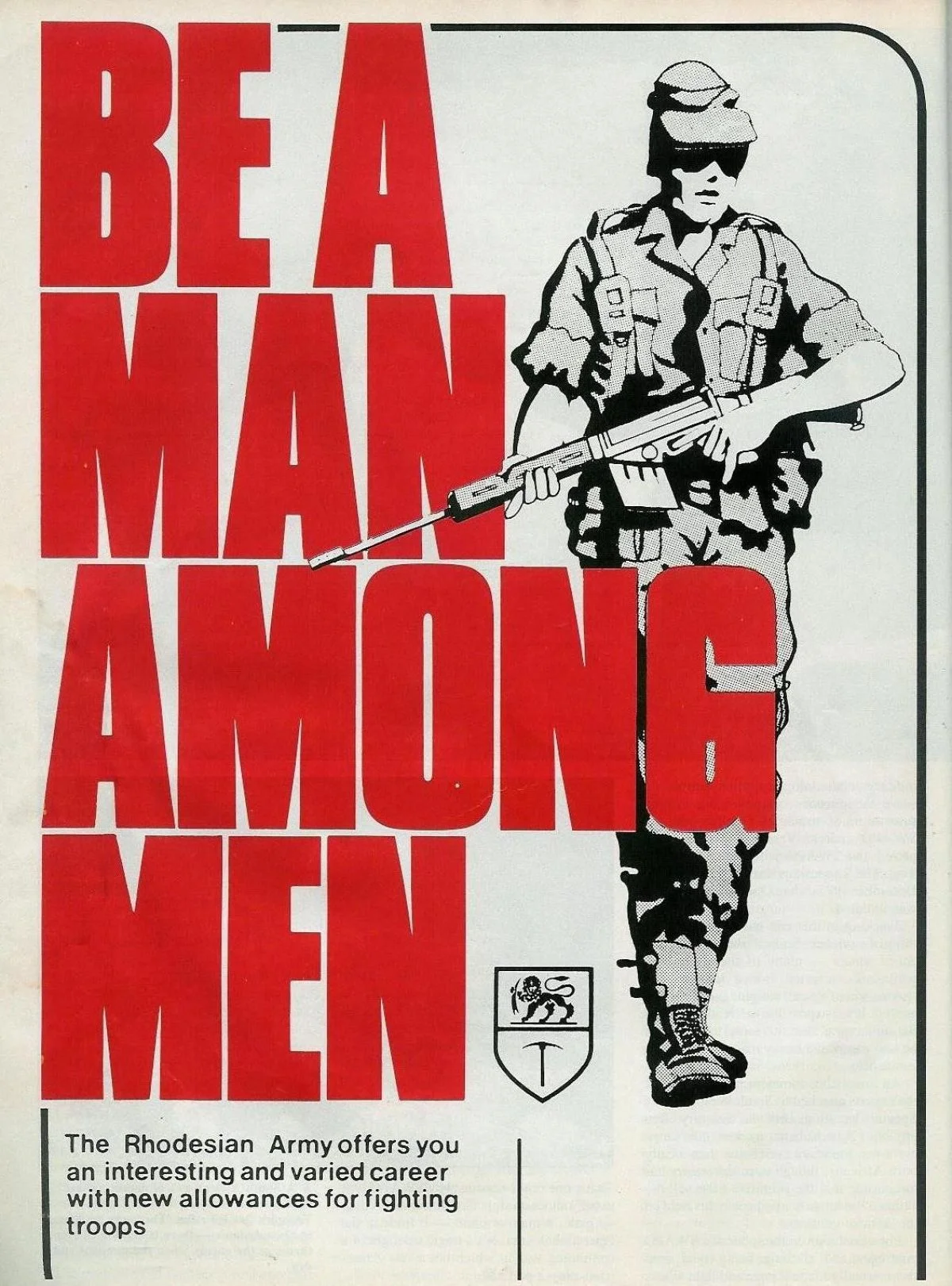

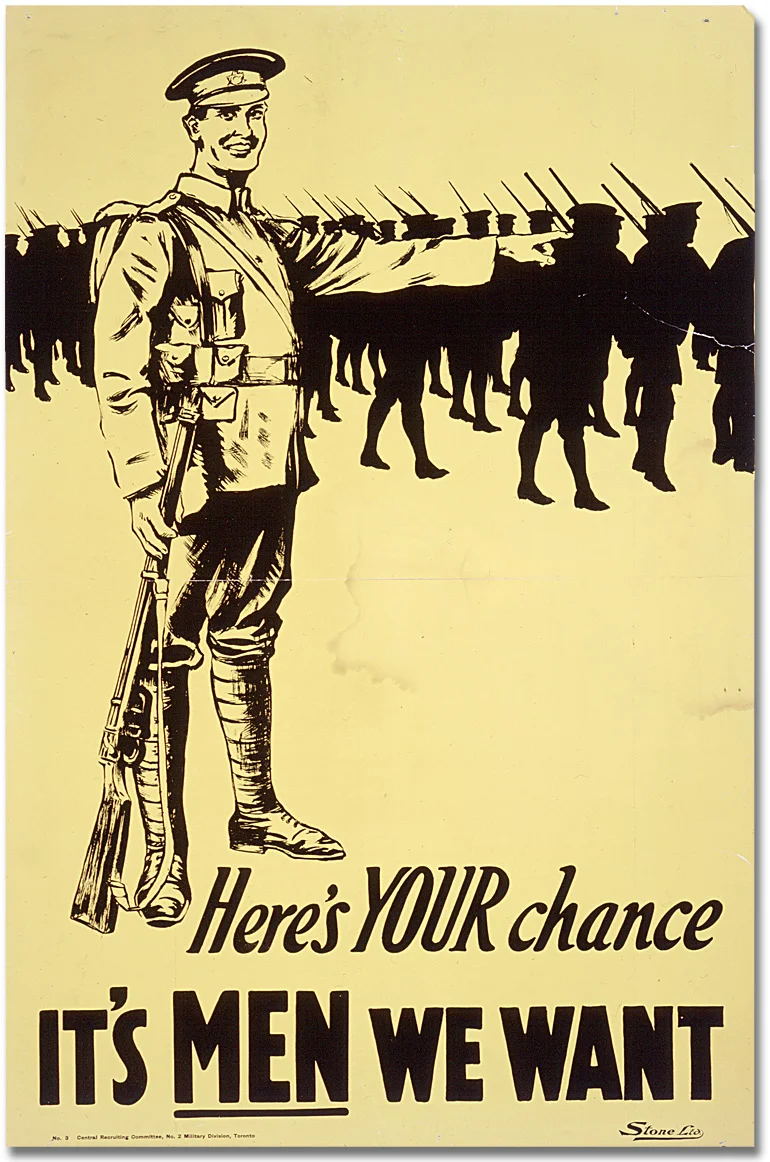

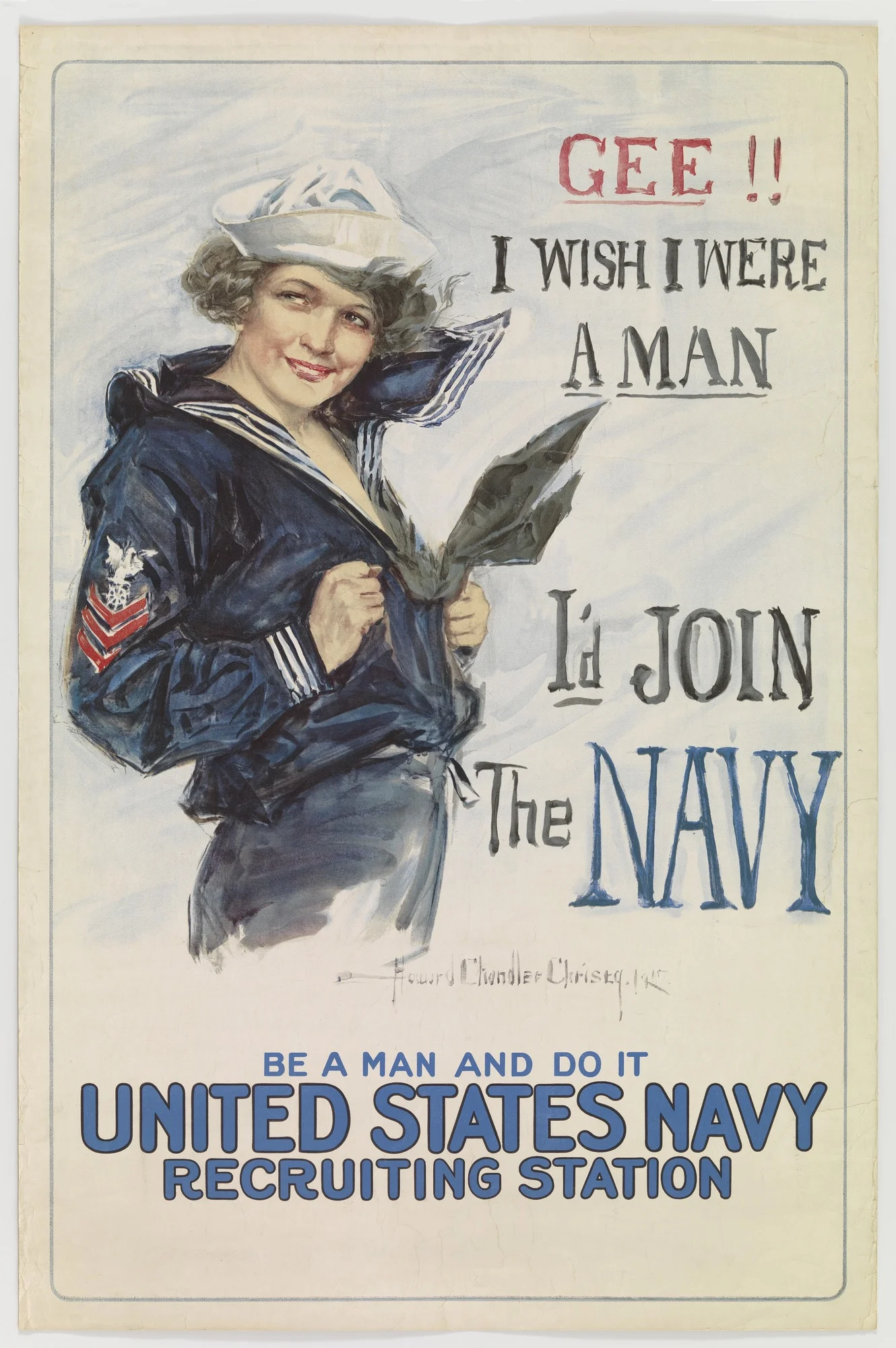

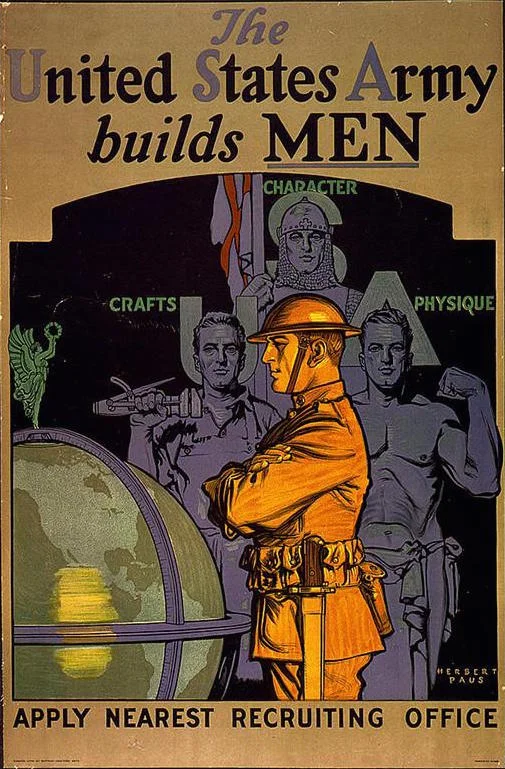

The set of warplay features some flyers, hung up on the fence that backs the stage. This flyer to the left, specifically -- for the Rhodesian Army. “BE A MAN AMONG MEN” they demand. I could spend a whole blog post on the exquisite art of subtlety in war propaganda, but I’ll just condense it to a few examples and leave it at this: the idea that a soldier must conform to this specific contemporary concept of masculinity is difficult to scrub away from the national consciousness; clearly — all three posters below are from the World Wars, and yet we’re still dealing with the same issues.

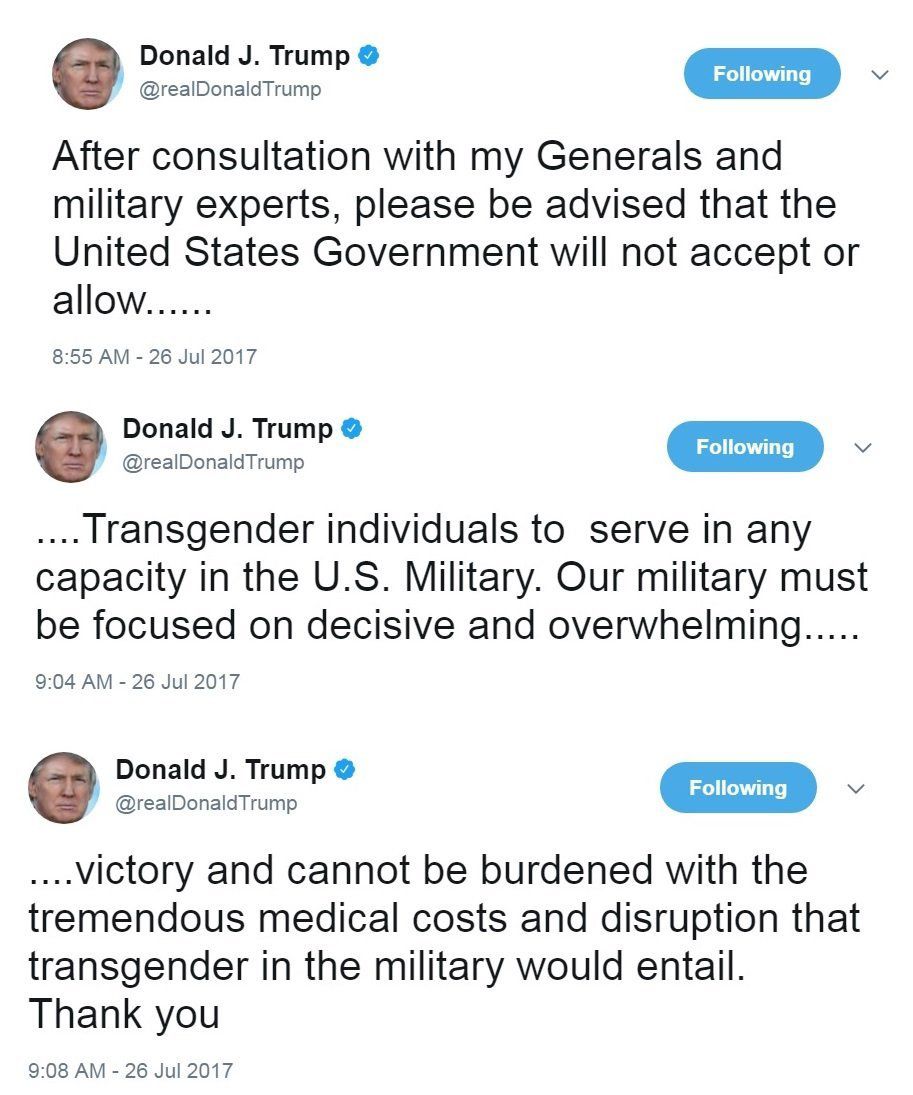

Obviously, none of this goes away when it comes to the issue of transgender soldiers. However, when it comes to the practical justification for discrimination, President Trump introduced a new angle in his tweets in July of last year, pictured here.

Worth noting -- the idea of “disruption”, of distraction, is still very much taken advantage of. The “tremendous medical costs”, however, is of course unique to “transgender persons with a history or diagnosis of gender dysphoria -- individuals who the policies state may require substantial medical treatment, including medications and surgery”, as a memorandum on the proposed ban says. Many fired back at the use of medical language to justify the ban, including the The American Psychological Association, which released this statement:

“[The Association] is alarmed by the administration’s misuse of psychological science to stigmatize transgender Americans and justify limiting their ability to serve in uniform and access medically necessary health care."

A New York Times article explained that “for many [transgender people]...the only continuing medical care they need are inexpensive hormone doses that they can administer themselves at home.” The point is also raised that many transgender people already serve right now in law enforcement and fire departments, obviously with no issue.

Kimberly Acoff; photo from Rolling Stone

But of course, the financial logistics of that don’t entirely matter, because Trump’s defense of his policy is meant to just cover up personal bias against both trans people in general, and specifically trans people in the military. And that ties right back to the stereotyping and constructs of gender and its relationship to war.

Kimberly Acoff, interviewed by Rolling Stone, is a transgender woman and veteran who had surgery before enlisting, and who did not reveal this fact to anyone in the military. She is also black, and recalled memories of lighter-skinned family members who, years ago, in order to find employment, had pretended to be white. She said, “I felt every pain that they felt. I was not afforded the privilege to proudly serve as my authentic self. This robbed me of [my] humanity.”

Authentic self. This speaks to the idea that a soldier is expected, whether by law or by public perception, to conform to an ideal -- that there’s an image to be maintained, an archetype to uphold. It’s an oppressive and troubling idea.

Within the first thirty seconds of warplay, A and P are arguing over this conformity. “The idea is antiquated,” P says, “...the expectation that I should just...Perform this role.” The role of a man? The role of a soldier? What defines each, and how do the strict assignment of those definitions affect the lives -- and the identities -- of those whom are supposed to, as P says, perform that? Well, we’re seeing that in America. We’re seeing the answer, and it’s not the one we should want to hear.

Photo by Johanna Austin / www.AustinArt.org

Our own preconceptions and expectations are something we need to be cognizant of as we watch gender and military politics evolve, during this administration and whatever comes after. They can seem large, lofty ideas about warriors, and identity, but there are individual people at stake every day. People just in search of an authentic self.

warplay closes this weekend -- to catch this story and see what it brings to the discussion for you, reserve your tickets here.

- Lucas