#MeToo Part II: Boys Will Be Boys Will Be Boys

This is Part II of a series of blog posts examining facets of the #MeToo movement. You can read the first part here.

Content warning: This post contains discussion of sexual assault.

Last week I introduced a three-part examination of elements of the #MeToo movement, and focused on victims of sexual assault that the movement, despite good intentions and positive outcomes, still marginalizes, such as sex workers and women of color. Different women are held to different standards when it comes to assault; some were “asking for it”, people will say. Others, like incarcerated women, are so dehumanized that disturbing defenses aren’t even offered.

Of course, women and victims are not the only ones held to problematic standards. One phrase is thrown about repeatedly during cases of sexual misconduct perpetrated by men, very recently and notably during last fall’s Brett Kavanaugh hearing: “Boys will be boys.”

There’s not much to be written about “boys will be boys” that hasn’t already been said, whether by op-eds, or protestors, or the viral Gillette ad. It’s toxic, it’s dangerous — basically, we need to stop saying it. But...where did the phrase actually come from? And what does #MeToo mean for it?

The origin of “boys will be boys”

Part of the problem with “boys will be boys” is that it’s such an old-fashioned idea. It even sounds old-fashioned. Unfortunately, to this day, it’s still ingrained in the American social vernacular. But words don’t just appear from nothing — and knowing where they came from might help us make them disappear.

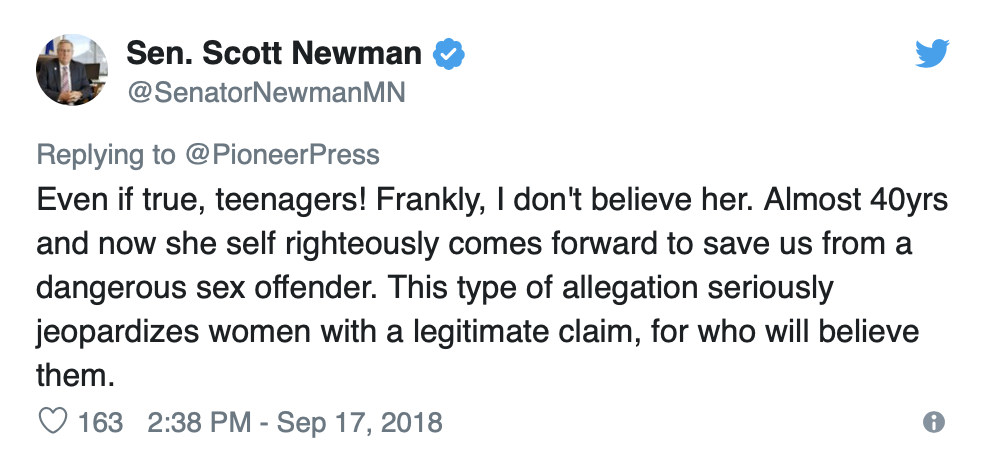

Ashwini Tambe is an Editorial Director for Feminist Studies and an Associate Professor in the Department of Women’s Studies at University of Maryland. For The Conversation, she’s written articles on #MeToo, and Trump’s effects on feminist movements. One of her pieces tackles “boys will be boys”, specifically in response to Kavanaugh. Something Tambe noticed is that a popular defense of Kavanaugh centered around his age. Take these tweets.

Tambe explains how the concept of “adolescence” as a distinct stage of growth in psychology, only first came about in the very early 1900s. She summarizes the 1904 coining by psychologist G. Stanley Hall; it’s a phase “between...12 and 18, encompassing the breaking of voice and facial hair for boys and the first menstrual period and breast development for girls — and the emotional maturation following these physical developments.”

G. Stanley Hall

As we all know, that emotional maturation comes with a few bumps in the road — except...our expectations of that come from Hall too. Tambe writes that “more than any other psychologist”, Hall emphasized the hormone storm of adolescence that we take for granted today. “His chosen constellation of features,” Tambe writes, “rebelliousness, emotional turbulence, sexual recklessness – became the blueprint for analyzing and assessing the problems of young people.”

So could it be that along with hormones making trouble for teenagers — our own expectations of what adolescence “should” look like are also to blame? Hall’s writings are controversial and Tambe cites other psychologists’ criticism, including Crista de Luzio’s point that “in the 17th century, youth was...a ‘relatively smooth’ period in New England Puritan culture in contrast to Europe…” Both societies have teenagers; only one conforms to Hall’s chaotic archetype of adolescent rebellion. Luzio attributes to the disparity to “social instability.” So -- physiology isn’t the only factor in teenagers “acting out.”

How does this all relate to “boys will be boys”? Well, as it turns out, Hall’s character of the rebellious, turbulent, sexually rash teenager...was, almost always, a young man.

But not only a young man. A young white man. A young, white, middle class man.

This model absolutely fit the bill for Kavanaugh’s case; defenders contextualize the alleged incident within what Tambe calls “a social tendency to see wealthy white boys’ actions as innocently naughty, rather than dangerous.” Violence against young black men shows the other side of the coin; without even committing crimes, they are inherently seen as more of a threat.

Brett Kavanaugh; There is “a social tendency to see wealthy white boys’ actions as innocently naughty, rather than dangerous.”

History and Gender Studies Professor Kristin Kobes Du Mez of Calvin College has spoken to the correlation between masculinity, race, and this model of adolescence — and why there is no equivalent “girls will be girls” statement. She says,

There was the fear that in the 20th century, men, especially white middle class and upper class men, might not be masculine enough anymore…They come up with that developmental model, where boys will be boys, that boys need to sow their wild oats, that they need to go through a ‘savage stage’ of development…After they experience that developmental stage in its fullness, then they will grow up, then they can develop some restraint, after somehow preserving this core of masculinity…

So not only did “boys will be boys” evolve out of now-outdated psychological expectations of adolescence, but its history is also racially charged. It frees wealthier young white men from accountability, while shaming and even victimizing women and people of color.

Missing the point: #NotAllMen

And so, we flash-forward to today. Despite the fallacious origins of “boys will be boys”, the phrase hasn’t gone away, although its publicity lately has been encouraging fuel for backlash against it. Most progressive minds see those four words for what they are, and refuse to accept them as a valid defense.

However, as we learned in last week’s post (and, you know, from life in general), some good intentions come with caveats. Some criticisms of “boys will be boys” seem to actually be missing the point, and may do more harm than good.

New York Times sportswriter Bill Pennington wrote an article in 2016 in response to Donald Trump’s infamous comments about sexually assaulting a woman were brushed off by his defenders as a common cousin phrase to “boys will be boys”: “locker room talk.” In it, Pennington explains that during his 30 years spent in actual locker rooms, he’s never heard talk that amounted to what Trump said.

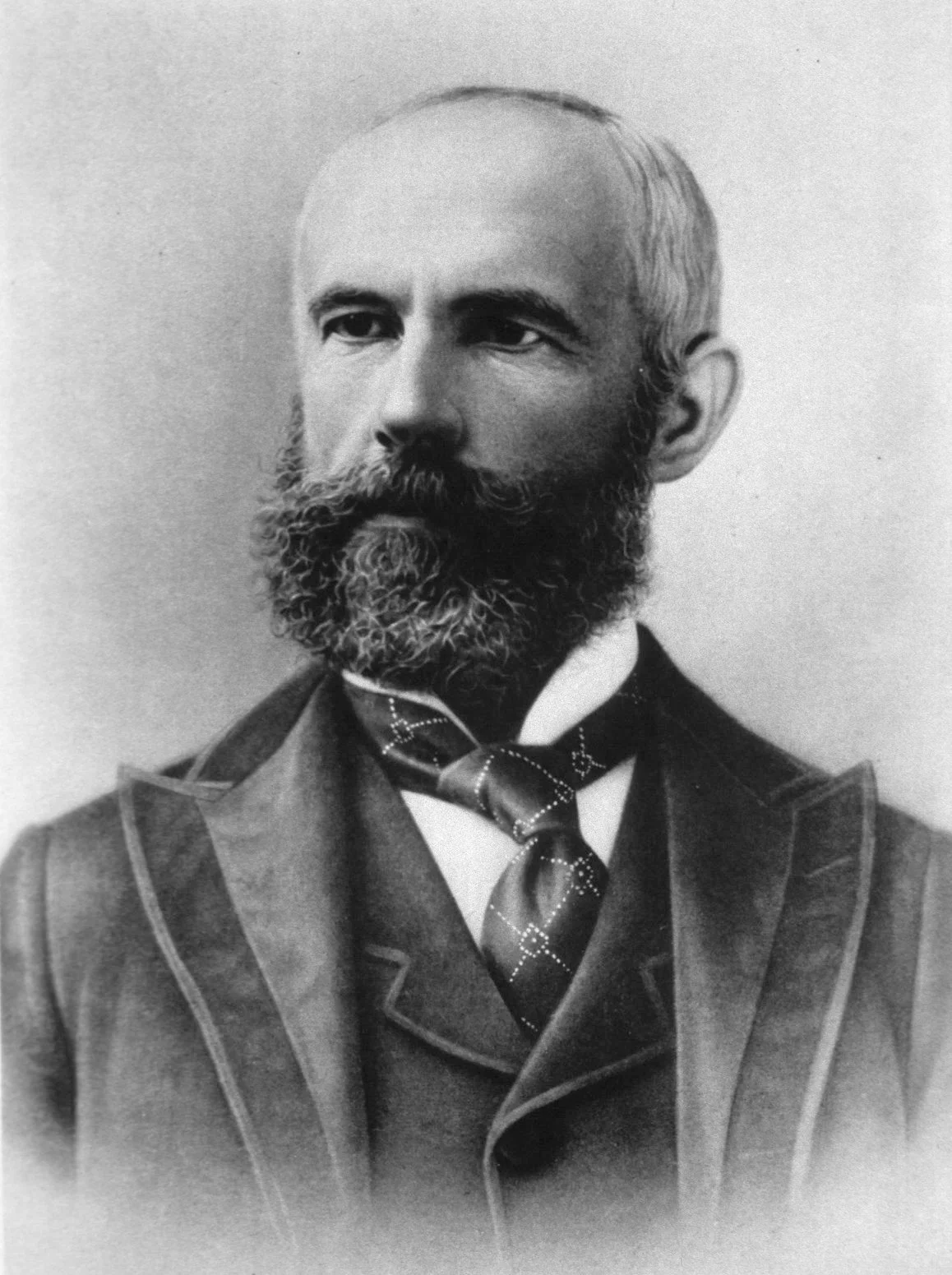

Two panels of a satirical comic featuring superhero “Not-All-Man”

by Matt Lubchansky; http://www.listen-tome.com/save-me/

This echoes a common critique of “boys will be boys”: Well my boys don’t do that...I don’t know any boys like that. The critiques seek to invalidate it on the basis that it’s a generalization, that it wrongly implies that all men engage in this behavior. On the surface, the sentiment is ostensibly positive; it supports the idea that behavior like Kavanaugh’s should not be taken for granted as something that “just happens, so deal with it.”

But it’s also a defensive stance, one that’s used to remove blame from some rather than focus blame on those who actually deserve it. Many men do act like Kavanaugh. Sexual assault against women is a pervasive problem, as #MeToo has only made clearer. Just because the behavior shouldn’t be taken for granted doesn’t mean it’s rare.

#MeToo

Finally, speaking of #MeToo...what does the movement really mean for “boys will be boys”? From the dubious psychologist who kickstarted the phrase, to the defenders who bandy it around, to the protestors who miss the mark: How has and will #MeToo make people say and hear “boys will be boys” differently? Well, in a lot of ways, #MeToo seems to be a direct reaction to those words.

To start, it’s drawing public attention to just how widespread sexual harassment and assault are —and, critically — it’s calling them that. More trivialized incidents that would fall happily under “boys will be boys” -- like workplace “flirtation”, drunken “roughhousing”, or catcalling — are being included along a spectrum of damaging behavior towards women.

But one of the strongest ideas that #MeToo will hopefully bring about (and one of the reasons why #NotAllMen is so dangerous) is that...often, in our society...boys will be boys. And that’s not okay. If the phrase is used at all, it shouldn’t be as a defense — but as an accusation.

Evelyn Nam is a representative to the Title IX Student Liaison Committee from Harvard Kennedy School. She writes in an article in the Kennedy School Review: “The vision of #MeToo…[is] the recognition that gender inequality is not the doing of a small subset of men. It’s [a] systemic, cultural injustice.” Like Tambe argues, it’s very possible men like G. Stanley Hall perpetuate expectations of rebelliousness and sexual recklessness in men, during their adolescence and even into adulthood. And ideas like that, compounded with male privilege, and white privilege, and economic privilege, create a culture that not only defends men like Kavanaugh, and Trump, but fosters them. The fact that “boys will be boys” exists at all is indicative of a desperate problem with masculinity in America — a problem #MeToo seeks to tackle head-on.

I saw a tweet around when #MeToo had erupted overnight; people were sharing their experiences all over. The tweet has always stuck with me. It said: “People who say ‘if that’s sexual harassment, then every woman I know has been sexually harassed’ are so close to getting the point.”

So much harmful behavior by men has been trivialized and brushed aside by a culture of “boys will be boys.” And the scary thing is, the phrase is designed to keep it that way. Boys will be boys. Grammarians would call it the future continuous. It’s something that we’re told we can reliably count on to keep happening. Boys will be boys will be boys. And unfortunately, given the deep roots of toxic masculinity and white male supremacy in America, that tense isn’t necessarily inaccurate. Like Nam explains, it’s systemic. Hopefully, that culture will change. Hopefully, future expectations of men, and young men in particular, will discourage these things from happening. As of right now though, they are happening — again and again. And rather than use that as a reason to give up, #MeToo asks:

Why are we okay with boys being boys?

- Lucas