Amazing Fantasy: Intellectual Property in Theatre

Azuka’s upcoming piece, MRS. HARRISON, written by R. Eric Thomas, has a lot going on. Sure, it features only two characters, who are confined to a single restroom for a single timeframe for the duration of the show, but the complexity of character, moral ambiguities, and thematic richness give plenty of layers to such a small space. Just one of the themes the play touches on is intellectual property. The entertainment industry is crawling with intellectual property disputes -- music is probably the first thing that comes to mind. But theatre has had its fair (or unfair, depending on which side of the lawsuit you’re on) share of cases.

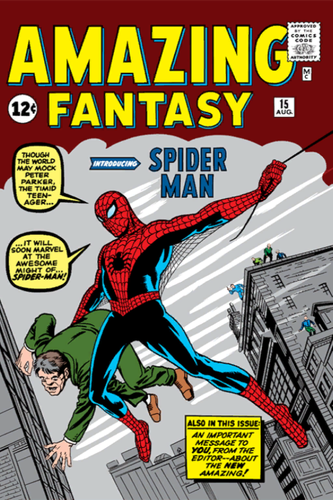

What’s the first rule of not only law, but also society as a whole? Don’t mess with Disney. In 2009, Disney made one of the biggest movies in their recent imperial history: purchasing multi-billion dollar fellow empire Marvel Entertainment, and they locked it down fast. Just four years later in 2013, American Music Theatre in Lancaster, PA staged Broadway: Now and Forever, a kind of retrospective and homage to iconic Broadway musicals. And as if it really needed any more controversy and legal issues on its plate, the infamous Spider-Man: Turn off the Dark was among the referenced pieces. Disney claimed “misuse of the character’s copyright- protected image and Spider-Man trademarks, which are used as set dressing, costumes, and advertising for AMT’s infringing production…”

But the web-slinging, leg-breaking reluctant Broadway hero isn’t the only issue Disney took with the show; the even more iconically Disney properties Lion King and Mary Poppins were also alluded to in Now and Forever. Definitely the most fun part about reading the Disney complaint is them explaining, for legal purposes, stuff pretty much everybody knows, like, say -- what a Mary Poppins is. “The Mary Poppins musical stage play and motion picture tell the story of the title-character, a sharp-tongued English nanny with magical powers that enable her to fly with the aid of an umbrella.” Ooh, that sounds cool. I might have to check that out. Wait, they even give a little synopsis. “Mary Poppins arrives one day at the home of the Banks family and becomes the caretaker of the family’s two misbehaving children – a boy and a girl. She proceeds to reform them as they experience a series of magical adventures on the streets of London, often in the company of Mary Poppins’s chimney sweep friend, Bert.” How quaint!!! How have I not heard about this sharp-tongued English nanny before?

American Music Theatre eventually relented, and destroyed the show’s costumes, props and sets.

I'm assuming that looked something like this.

But intellectual property isn’t just a point of contention between the smaller fish in the pond, and, say...what's a good metaphor for the happiest place on earth? One of those 70-foot prehistoric dinosaur sharks. Sometimes, it’s a lot more personal -- just two artists...and one idea.

The Glass Menagerie. That’s a thing -- Southern accents! Gentleman callers! ...Glass? I haven’t read it since high school. When a play is such a classic and has been around for so many years, people are bound to wanna spice things up a bit. That’s when you get startling interpretations like Hans Fleischmann’s 2012 Chicago production, wherein the show’s narrator Tom, a member of the central Wingfield family and shoe warehouse worker / wannabe poet, is actually “a delusional homeless man who lived in a city alley beneath a fire escape”, American Theatre reports. The play’s actual eponymous glass menagerie...is just broken bits of glass.

From Miller's Menagerie.

The idea’s bizarre. It’s potentially exciting, and also, you know, potentially an offensive exploitation of homelessness. But most prominently of all, it was unique. That is, until an artistic director in the Bay Area took Tennessee Williams's semi autobiographical memory play and did with it the

Exact.

Same.

Thing.

Homeless Tom Wingfield. Fire escape. Inspired by Miller’s own experience working near 6th Street, an alleged “homeless highway.” He claimed “the scenic design was completely inspired by the east stoop of our building”, not Fleischmann’s eerily parallel production. American Theatre writes, “After photos of Miller’s Menagerie appeared online, Fleischmann spotted them and consulted an attorney. ‘He said, ‘I hate to say this, but you have no legal rights in this situation,’’ Fleischmann recalled. “You can’t copyright an idea.’ That was the worst. I feel like such a victim.’”

You can’t copyright an idea.

Miller was attacked by the theatre community online for what they saw as clear intellectual infringement. “I lost friends and colleagues,” Miller saied, “and a dark cloud came to live over me and my theatre for a long time. I have had to work very hard to regain trust that I lost for absolutely no reason other than bad timing of a similar production concept.”

But probably my favorite case that I came across while reading up on this stuff revolves around another classic: A Midsummer Night’s Dream. I was IN A Midsummer Night’s Dream, so I’m pretty much an intellectual property law expert. Wait, what? In 2016 set designer Bob Lavallee made a really cool and big tree to be at the center of a Midsummer production at the Trinity Shakespeare Festival. Steve Jones from from Lyric Stage in Dallas was like, Hey. That’s a really cool and big tree you got there. It would be a shame if something were to………………………………….happen to it. Lavallee told him he could use the set piece in Lyric’s Camelot for a price of a couple hundred dollars and a program credit -- fair enough. But Steve Jones said, Thanks, but I’m gonna do something………………………………….else.

Lavallee's A Midsummer Night's Dream (Fred)

Jones' Camelot (George)

Not only did Jones co-opt the tree for use in Camelot without paying or crediting Lavallee -- he ended up repurposing even more of the set -- a platform, doorway, drapery -- Lavellee admitted, in a quote both hilarious and a little terrifying, “I really don’t know how the entire set ended up over there.”

That’s not necessarily even the part of the story that stood out to me most. Because Steve Jones wasn’t even the one credited for the stuff he stole -- that honor went to “Cornelius Parker.” Voted Most Likely to Be A Pseudonym in high school, Cornelius Parker never went to high school, because he wasn’t real. Of the fake name, Steve Jones told a local arts publication --

“I didn’t want to take credit for it.”

This is a weird subject. It’s such a weird subject. Isn’t it? The ownership of things ranging from concrete (the rights to an iconic established character), to nebulous thoughts (allegedly independently-developed yet identical interpretations of the same piece of art). Like Fleischmann’s lawyers told him, “You can’t copyright an idea.” But...can’t you?

Or can’t you?

And what’s the motivation behind stealing another person’s work...and not even taking the credit for it? Who are you serving?

The topic of intellectual property is rich with controversy and ambiguity. It’s why it makes such a genuinely fascinating and thought-provoking theme in MRS. HARRISON. MRS. HARRISON, a play -- a piece of art -- that presumably started out as the germ of an idea in the mind of a creative man -- and somewhere, somewhere strange, along the way -- became his idea. If it ever even did.

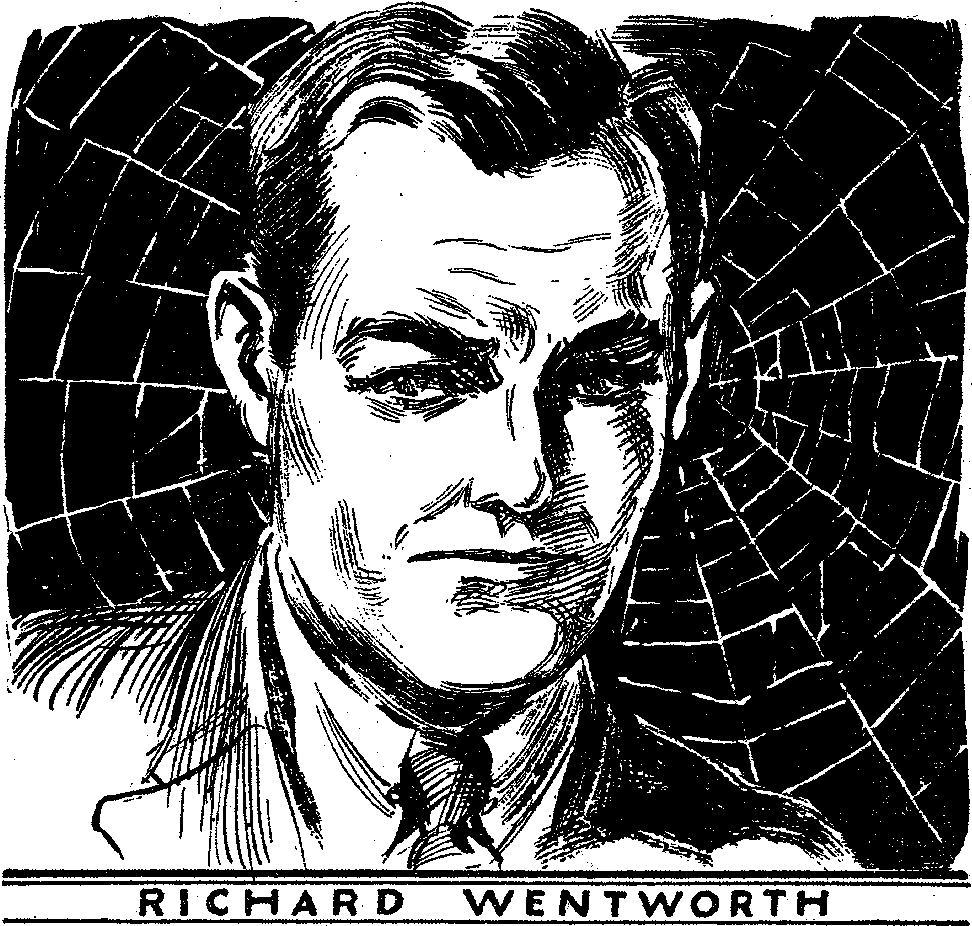

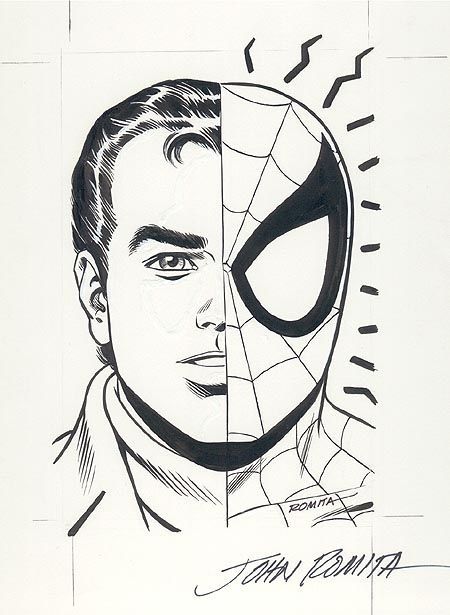

I’m a comic book geek, no shame. I can tell you without a glance at Wikipedia that in 1933, Harry Steeger created a pulp-magazine vigilante named Richard Wentworth -- “The Spider.” Thirty years later, in their Amazing Fantasy title, Marvel Comics debuted Spider-Man, and Marvel godfather Stan Lee admitted to being inspired by The Spider. And at the time, parallels were also drawn to another comic character called The Fly; in fact, elements of the Spider-Man mythos were purposely changed to avoid too much comparison. But hey -- regardless of what inspired the idea, Stan Lee created Spider-Man...or was it his creative partner, Jack Kirby? Or the comic’s inker, Steve Ditko? In the book Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko, Ditko would later admit “I still don't know whose idea was Spider-Man.”

Marvel owns Spider-Man. Disney buys Marvel. Disney sues AMT for stealing their property.

And for the record…“Richard Wentworth” would also be a really obvious pseudonym.

See you next week,

Lucas

Articles:

"Property Rights and Wrongs" by Jenn McKee

https://www.americantheatre.org/2018/01/19/property-rights-and-wrongs/

"Disney Sues Over Musical Featuring 'Spider-Man,' 'Mary Poppins' and 'The Lion King'" by Eriq Gardner

https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/thr-esq/disney-sues-musical-featuring-spider-637362